According to Greek mythology, Hades is one of the three great divine domains: while, after battling with the Titans, Zeus received the heavens and Poseidon the sea, their brother Hades had to be satisfied with the eponymous underworld. Only the earth as the realm of human beings and Mount Olympus, which was reserved for the gods, were not ruled in a dictatorial manner.

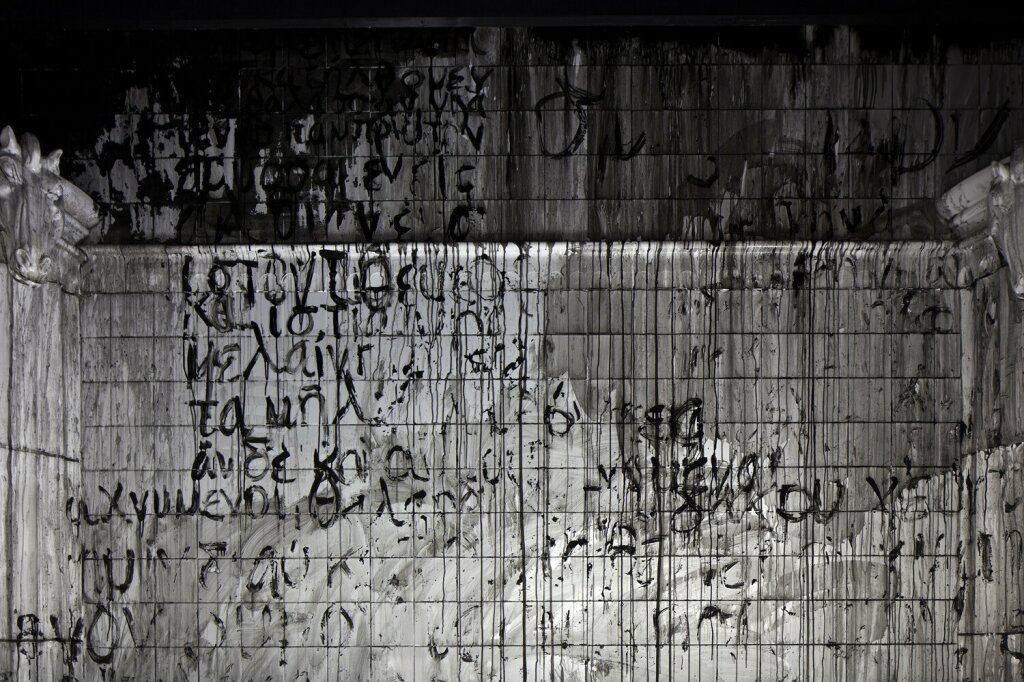

In contrast to these place-bound gods, the multifaceted Hermes, messenger of Zeus, protector of travelers, merchants, and herdsmen, god of thieves and oratory, is at home every here, his métier being the in-between. As a mediator between worlds, he also accompanies the dead on their journey over the Styx into the eternal realm of shadows. There flow the two rivers Lethe and Mnemosyne, whose waters, on the one hand, erase people’s memories upon their arrival and, on the other, grant them access to all knowledge in the world.

Unlike the Christian concept, which associates the underworld with hell and the heavens with paradise, the Greeks situated Elysium in the (at first value) neutral Hades: the souls of people were able to forget all earthly suffering on the island of the blissful, around which the Lethe flows. There, dying at first only implied entering the eternal present; death liberated human beings from painful memories and cancelled out history.

At the same time, the muses as daughters of Mnemosyne also have their origin in Hades: the nine sisters embody the arts of antiquity, with whose help human beings establish a relationship with their surroundings and past and make this relationship productive.

Hades therefore denotes an intersection at which remembering and forgetting, present and past, eternity and ephemerality meet and exist in parallel. Insofar, the Hades in Müller’s œuvre could be described as a spatial counterpart to Hermes, which, as an intermediate zone of two mutually exclusive properties, is simultaneously both and neither of the two. In this sense, the museum as a place and artwork as an object follow in this tradition—they are not only a temple of the muses or a reference to a higher order, but instead also places and things that simultaneously produce remembering and forgetting and draw their energy from this interplay.